Fitzgibbon, James W. (1915-1985)

Variant Name(s):

James Walter Fitzgibbon

Birthplace:

Omaha, Nebraska, USA

Residences:

- Pennsylvania

- Norman, Oklahoma

- Raleigh, North Carolina

- St. Louis, Missouri

Trades:

- Architect

NC Work Locations:

Styles & Forms:

Modernist

One of the founding faculty members of the School of Design at North Carolina State University, a pioneer in the design and fabrication of geodesic structures, and a talented residential designer, James W. Fitzgibbon (August 6, 1915-April 7, 1985) exemplified the spirit of architectural innovation that blossomed in the United States in the mid-20th century. Working with a variety of collaborators, he created a varied but distinctive body of architectural work that helped shape Raleigh’s image as a center of modernist design.

James Walter Fitzgibbon was born on August 6, 1915, in Omaha, Nebraska, where his father Frank was working on a construction project as a subcontractor. The family returned to upstate New York where Fitzgibbon completed studies at Onondaga Valley Academy in 1932. The following year he graduated from Syracuse Central High School. Fitzgibbon attended the Syracuse University School of Architecture, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1938, receiving the Gifford Design Prize. In 1939 he earned a Master’s Degree from the University of Pennsylvania where he won the Warren Prize design competition and was a finalist for the Rome Prize. Fitzgibbon married fellow Syracuse student and artist Margaret Inez Crosby of Falconer, New York, in 1940.

Architectural offices in the late 1930s were still suffering from the effects of the Great Depression, and unable to find an architectural position, Fitzgibbon went to work as an architectural designer with United Engineers and Constructors of Philadelphia, a major contractor of industrial complexes and manufacturing plants. The four years that he spent planning these facilities served to acquaint him with industrial materials and building methods and strongly influenced the course of his later architectural career.

Fitzgibbon passed his architectural licensing exam in 1943 and was registered as an architect in Pennsylvania. Laid off in 1944 as war-related construction came to a halt, he used his Philadelphia connections to help him secure a position as a campus planner at the University of Oklahoma, where an expansion of the campus was anticipated. The rapid growth of the architectural program post-World War II caused Fitzgibbon to be drafted into service as an assistant professor in 1945. However, conflicts with the administration of the engineering school, wherein the architecture program was located, caused a group of professors led by department head Henry Kamphoefner to look for another professional home.

In 1948, Kamphoefner and a group of faculty and students including Fitzgibbon left Oklahoma to establish what would become the School of Design at North Carolina State University. Fitzgibbon served as the associate architect for campus planning and initially as an assistant professor of architecture before becoming a full professor in 1953.

On his way to Raleigh in the summer of 1948, Fitzgibbon met theorist and engineer R. Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College near Asheville, where Fuller was conducting experiments in the development of geodesic domes with students. A term coined by Fuller, “geodesic” refers to a spherical or partial spherical lattice shell based on a network of great circles or geodesics that intersect to form triangular elements that have both local triangular rigidity while also distributing stress across the entire structure. Although others had experimented with similar structures, Fuller developed the intrinsic math of the dome, for which he received a patent in 1954.

When Fuller came to Raleigh to lecture in 1949, Fuller and Fitzgibbon began a long partnership, beginning with Fitzgibbon serving as the head of the International Fuller Research Foundation (1949), then as a business partner in Skybreak Carolina Corporation (1952). In 1954 they formed Geodesics, Inc., to design and construct geodesic domes for the Marine Corps, and Fitzgibbon took a break from his academic career. In 1957, Fuller and Fitzgibbon formed Synergetics, Inc., to focus on commercial projects.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Fitzgibbon, Fuller, architect/engineer Thomas C. Howard, Pete Barnwell, Duncan Stuart and other members of Synergetics developed the basic Fuller concept into a functional and versatile set of building systems. Synergetics focused on industrial architecture and geodesic dome applications for military, governmental and commercial clients, including the United States Navy, the United States Information Agency, the Canadian government, Ford Motor Company, and the Kuwaiti Government. In 1956, under contract to the United States Department of Commerce, a 100-foot diameter trade fair pavilion dome was designed and test-erected in Raleigh, then flow to Kabul, Afghanistan. This dome was later used by the United States’ trade fairs and expositions in South America, Africa, Europe and the Orient. A 125-foot diameter hemisphere was designed for use by Queen Elizabeth II when she visited Ghana, and various other domes went to the Air Force Academy, the 1961 Seattle and 1964 New York World’s Fairs, and to Cleveland, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Niagara Falls. In 1956 the firm designed and built what was at the time the world’s largest free-span structure, a 384-foot diameter geodesic dome in Baton Rouge, Louisiana constructed for the Union Tank Car Company as a facility to house and repair railroad cars. Another of their more notable projects was the 1960 Climatron geodesic dome at the Missouri Botanical Garden.

In 1967, Fitzgibbon returned to the School of Design. The following year, he took a leave of absence from Synergetics to teach as a visiting professor of architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, where he remained for the rest of his career, also acting as a visiting professor at other schools, including the University of California at Berkeley and Harvard. Fuller and Fitzgibbon continued to work together in the early 1970s on ventures like the Old Man River Project, an $800 million concept to house 30,000 to 50,000 people under a massive geodesic dome in East St. Louis, Illinois.

While most of Fitzgibbon’s professional production focused on industrial and governmental projects, he also designed a number of distinctive residences. The first of these, in 1947, was a concrete “desert house” for his brother Francis Joseph in Pojoaque, New Mexico. During the summer before moving to Raleigh, he designed the Kirby-Smith House and Cleveland House (1948-49) in Sewanee, Tennessee and the Daniel House (1950) in Knoxville, Tennessee. The Daniel House is perhaps his best-known residential design, incorporating as it does segments of surplus Quonset huts in a soaring double vault accented with marble, plywood and wormy chestnut finishes.

The houses that Fitzgibbon designed in North Carolina exhibited the strong influence of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work of the previous two decades, including both his romantic, organic approach to architecture, and his utilitarian Usonian house concepts of the 1930s and early 1940s. Fitzgibbon echoed Wright’s interests in modular design, in the use of low-cost, mass-produced industrial materials and techniques for constructing housing, in passive solar climate control, and in the integration of buildings into the site. His houses also incorporated organic materials like stone, artfully-shaped copper, and natural woods.

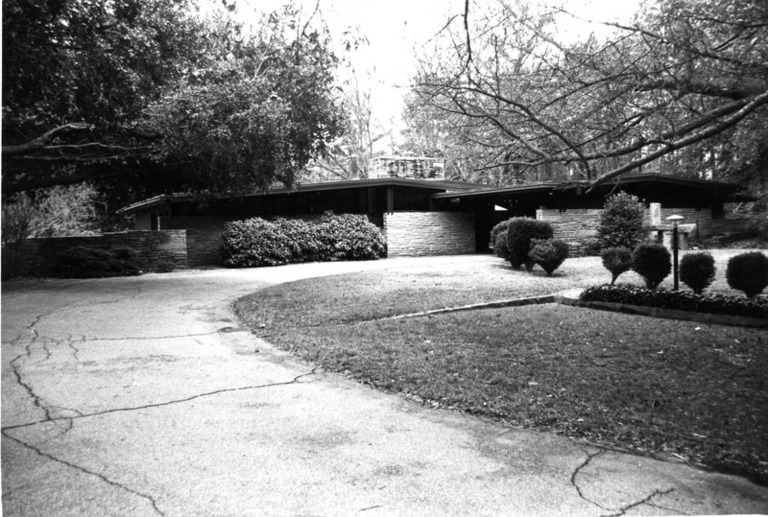

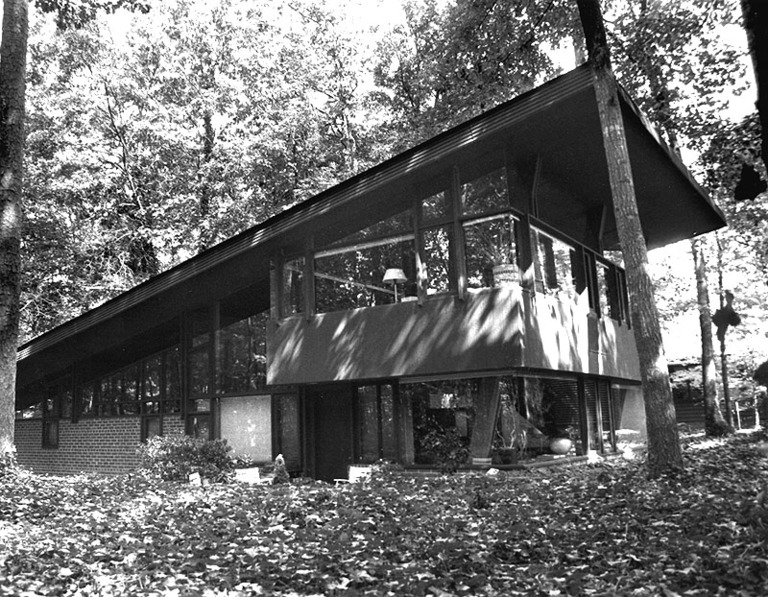

Fitzgibbon’s two principal Raleigh designs, the Ralph and Nancy Fadum House (1950) and the George and Beth Paschal House (1950) demonstrate related but differing strands of his work. Published in Architectural Record in 1951 as one of the Houses of the Year, the Fadum House is a wedge-shaped house partially sunk into the hillside with deeply-overhanging eaves and large expanses of south-facing glazing. Built on a modular structural grid, the multi-level house displays finishes throughout of exposed brick and stained and sealed plywood or tongue and groove pine, cypress or redwood. The Pachal House is larger, but all on one level. It has a more complex, lyrical form composed of multiple, swooping, low-sloped gables that unite on the garden side into one all-encompassing gable. Inside and out, the Paschal house has a richer palette of random ashlar granite with pine and natural-finished plywood of a variety of veneers. In addition, Fitzgibbon planned a few modernist residences in Winston-Salem, which continued the themes seen in his Raleigh work, including the Dr. Fred and Edna Garvey House, designed for the parents of one of his students.

Fitzgibbon was also a talented painter and draftsman. His drawings, paintings and architectural designs were exhibited in galleries and museums, including the St. Louis Art Museum and the Museum of Modern Art.

On April 7, 1985, Fitzgibbon died in his sleep at home in St. Louis at the age of 69.

- Peter Calandruccio, “James Fitzgibbon’s Daniel House,” Fine Homebuilding, No. 33 (June/July 1986).

- Architectural Registration file for James W. Fitzgibbon, North Carolina Board of Architecture, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Biographical Sketch, Fitzgibbon Papers, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, Missouri, http://www.mohistory.org/exhibits/Fitzgibbon/biography.aspx.

- “House in Raleigh, North Carolina,” Architectural Record, 110 (Oct. 1951).

- Charles Kahn, unpublished interview with James Fitzgibbon, St. Louis, Missouri, Dec. 22, 1976.

- George Smart, “James Walter Fitzgibbon,” Triangle Modernist Houses, http://www.trianglemodernisthouses.com/fitzgibbon.htm.

- Elizabeth C. Waugh, North Carolina’s Capital, Raleigh (1967).

Dr. Fred and Edna Garvey House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architectDates:1952

Location:Winston-Salem, Forsyth CountyStreet Address:440 Fairfax Dr., Winston-Salem, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Fitzgibbon House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architectDates:1948

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:617 Kirby St., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:For his own residence, Fitzgibbon remodeled an existing residence.

Florence Francis House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architectDates:1968

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:1515 Battery Dr., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

George and Beth Paschal House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architectDates:1950

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:3334 Alamance Dr., Raleigh, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Residential

Images Published In:Elizabeth C. Waugh, North Carolina’s Capital, Raleigh (1967).

Note:Despite extended efforts by preservationists to save it, the house was razed in 2013. See Raleigh News and Observer, March 2, 2013 for comments from the owner and local preservation advocates.

Gilbert and Nora Gottlieb House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architectDates:1968

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:4908 Forestville Rd., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Ralph and Nancy Fadum House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architect; Frank Walser, builderDates:1950

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:3056 Granville Dr., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Winston Roberts House

Contributors:James W. Fitzgibbon, architectDates:Ca. 1952

Location:Winston-Salem, Forsyth CountyStreet Address:271 Canterbury Tr., Winston-Salem, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential