Tilton, Edward L. (1861-1933)

Birthplace:

New York City, New York, USA

Residences:

- Asheville, North Carolina

- Durham, North Carolina

Trades:

- Architect

NC Work Locations:

Building Types:

Styles & Forms:

Beaux-Arts

Edward L. Tilton (1861-1933) was a Beaux-Arts trained architect who specialized in libraries in an era when many American cities and colleges sought up-to-date and imposing library buildings. He gained practical experience working in the office of McKim, Mead and White, American masters of the Beaux Arts mode and attended the École des Beaux Arts in 1887-1890. Beginning his architectural practice in New York in 1891 with William A. Boring, he designed dozens of libraries during his long career as well as other governmental facilities. Many of these are in the northeastern United States, but there are some in other regions. He is credited with four public libraries in North Carolina—in Winston-Salem, Durham, Henderson, and Asheville. Each was the pride of its community when built, and all still stand.

The early 20th century was a busy period of library construction, including both public libraries in communities and libraries for colleges and universities. In keeping with Progressive Era values, library construction and improvement projects were encouraged by the North Carolina Library Commission. Many were funded in part by the Carnegie Foundation as well as by local donors. The Durham Morning Herald of July 6, 1921, explained, “There is no institution of more value to a community than a well-equipped and well-conducted public library. It has something that appeals to all classes, from the first grade school children to the aged men and women who are sitting in the glow of the fading sun of life.” Most of these were restricted to white users, given the era’s adherence to Jim Crow segregation policies; a few libraries were also built for black citizens and colleges.

In this period, North Carolina clients commissioned many buildings from local and regional architects who planned a wide range of building types from residences to skyscrapers. In some cases, though, they, like other clients, turned to nationally active architects who specialized in certain building types: Ralph Adams Cram, for example, for his Gothic Revival churches; Charles R. Makepeace and others for industrial architecture; and William Lee Stoddart for modern hotels and other tall building. By commissioning a library from Edward Tilton, leaders in Winston-Salem, Durham, Henderson, and Asheville placed their communities in the national architectural mainstream as well as asserting the importance of reading and education for their citizens.

According to a monograph on Tilton, the first of his designs in North Carolina was the Winston-Salem Carnegie Public Library in 1904. A Carnegie library authorized in 1902 was built in 1904-1905, with $15,000 in Carnegie funds and a local government appropriation. (The monograph also includes the Durham Public Library but not those in Asheville or Henderson.)

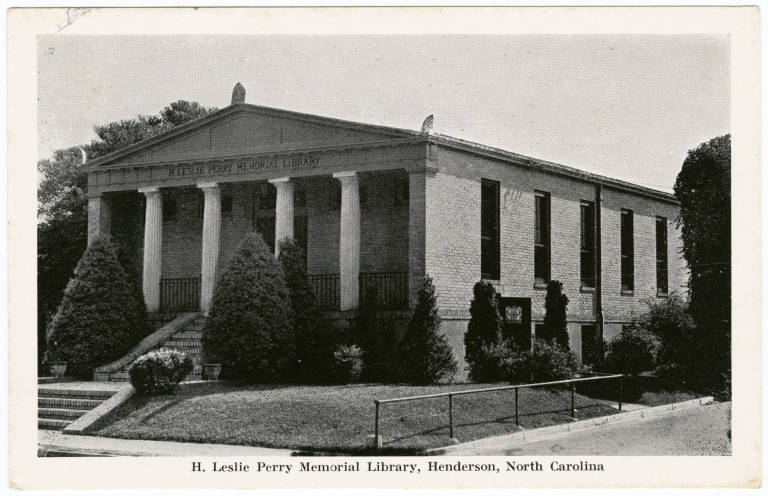

In the early 20th century, Durham leaders were commissioning new buildings in classical modes to replace the eclectic architecture of the late 19th century, and in many cases they employed nationally active architects for the purpose. The tobacco city had a Queen Anne-style library built in 1897, but local sponsors led by businessman T. B. Fuller gained financial assistance from the Carnegie Foundation to build the modern if relatively modest, neoclassical Durham Public Library (1921) in sandstone-colored brick from a design by Tilton at a time when he was associated with another architect, Alfred Morton Githens. Not long after this, a local family in the tobacco town of Henderson donated to Vance County a neoclassical facility designed by Tilton—the H. Leslie Perry Library (1924), which takes a temple form with a Doric portico. It was given in memory of a young local attorney, H. Leslie Perry, by his parents and widow.

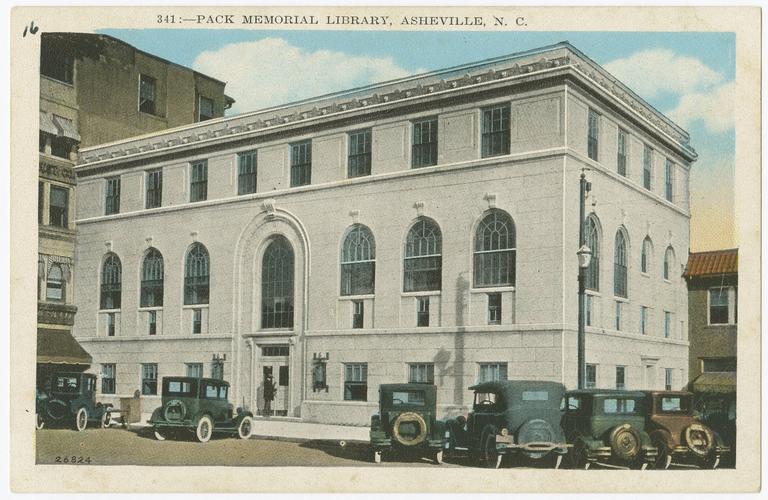

The fourth, and by far the grandest, of Tilton’s known libraries in North Carolina rose in the mountain city of Asheville in 1925-1926 during that city’s construction boom, which included public as well as private projects. Located on a prominent site overlooking Pack Square, the neoclassical Pack Memorial Library II replaced a castellated library. The earlier building, said to have been built as a bank, was given in 1899 by lumberman George W. Pack to the Asheville Library Association and subsequently named for him (Asheville Citizen-Times, Dec. 8, 1918). The Asheville facility was described in the 1910s as having the largest book circulation of any public library in North Carolina. The Citizen-Times said in 1918 that the library association found it was not well arranged for library use and considered selling it and building a new facility elsewhere. In the event, however, the new library was built on the almost same site as the older one. (Some accounts say the earlier structure burned in 1923; Asheville newspapers for the mid to late 1920s are only sparsely represented in newspapers.com.) In any case, the new library was an imposing and stylish edifice. The 3-story, marble-faced edifice is composed as a Renaissance Revival palazzo with dramatic arched openings. The open plan followed the models of the day. The library, like the square, is named for the older library’s donor, who also sponsored the Vance Memorial that anchors the square.

- Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (2003).

- Catherine W. Bishir, Michael T. Southern, and Jennifer F. Martin, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Western North Carolina (1999).

- Lisa B. Mausolf and Elizabeth Durfee Hengen, Edward Lippincott Tilton: A Monograph on His Architectural Practice (2007), https://www.nh.gov/nhdhr/publications/documents/etilton_monograph.pdf.

Durham Public Library

Contributors:Edward L. Tilton, architectDates:1921

Location:Durham, Durham CountyStreet Address:311 E. Main St., Durham, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Public

Images Published In:Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (2003).

Note:The neoclassical library replaced a Queen Anne style library of 1897. Local leaders, especially businessman T. B. Fuller worked long and hard to obtain Carnegie funding for the new “first class library” facility (Durham Morning Herald, Nov. 10, 1916, July 8, 1921). The Durham Morning Herald of March 31, 1921, declared that the new library “is a beauty. It has all the modern improvements and conveniences of a building that is believed will please the public in every particular.” It was reported in the same paper on September 27, 1917, that the Carnegie fund would provide $32,000 and the local library board expected to realize at least $8,000 from the sale of the old library and property at Five Points.

H. Leslie Perry Library

Contributors:Edward L. Tilton, architectDates:1924

Location:Henderson, Vance CountyStreet Address:Young St., Henderson, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Public

Note:Henderson citizens had sought a public library for some time before a donation from a local family made it possible.

Pack Memorial Library II

Contributors:Edward L. Tilton, architectDates:1925-1926

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:S. Pack Square, Asheville, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Public

Images Published In:Catherine W. Bishir, Michael T. Southern, and Jennifer F. Martin, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Western North Carolina (1999).

Note:The former Pack Memorial Library is now the Asheville Art Museum. The present Pack Library occupies a newer building several blocks away.

Winston-Salem Carnegie Public Library

Contributors:Edward L. Tilton, architectDates:1904-1905

Location:Winston-Salem, Forsyth CountyStreet Address:Corner of Cherry St. and 3rd St., Winston-Salem, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Public

Images Published In:Heather Fearnbach, Winston-Salem’s Architectural Heritage (2015).

Note:After a new downtown library was built on West Fifth Street in 1953, the small Carnegie library was purchased to serve as a Catholic church.