Bishop, George (1824-1901)

Birthplace:

New Bern, North Carolina, USA

Residences:

- New Bern, North Carolina

Trades:

- Manufacturer

- Contractor

- Carpenter/Joiner

NC Work Locations:

Building Types:

Styles & Forms:

Gothic Revival; Italianate

George Bishop (1824-1901) was a New Bern house carpenter and furniture maker who pioneered the mass production of construction materials in North Carolina in the years shortly before the Civil War. Although he became primarily a manufacturer, he continued as a contractor and builder through most of his life. His career exemplifies an important pattern in American construction history—the transition from artisan to manufacturer often propelled in its early stages by artisans themselves. This transition, of course, would soon alter the traditional roles of carpenters and joiners in the industrial age. Bishop is also of interest because of the role he took in emancipating an enslaved man, John Good, in a time when private manumissions had become extremely difficult in North Carolina.

Little is known of Bishop’s training or early career. He was a native of New Bern and a son of wheelwright Samuel Bishop. Although evidently not listed in the 1850 census, George Bishop was recorded in the 1860 United States Census as a mechanic, aged 30 (probably not correct; his grave marker gives his birthdate as 1824), and head of a household that included his wife, Eliza J., and children George Jr., Julia, and Elizabeth, aged 7 to 2, plus two carpenter’s apprentices and a free black domestic servant. (The term “mechanic” referred to a number of skilled occupations, including that of a house carpenter.) Bishop owned $5,000 in real estate and $10,000 in personal property, which likely included equipment and materials. He was also active in civic life and, not surprisingly, in 1858 he served on the committee to plan a celebration for the long-awaited completion of the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad to New Bern, which boosted local enterprise including the market for his products.

According to New Bern memoirist John D. Whitford, Bishop’s work as a builder included several brick and frame structures over a long period. He took apprentices to both the house carpenter’s trade (in 1851) and the cabinetmaker’s trade (in 1854). He is best known for the 1871-1875 rebuilding of Christ Episcopal Church after a fire in 1871. In 1885-1888 he built a block of two brick stores, the George Bishop Stores, at present 240-242 Middle Street in downtown New Bern, to replace a similar building that burned in the town’s great fire of 1885. A few years later, the Daily Journal of April 29, 1890 reported, “A handsome dwelling house is being erected on the lot on George street, near Pollock, for Mrs. W. H. Pennell, of Philadelphia. Mr. George Bishop is the contractor.” Bishop likely constructed numerous other buildings as yet unidentified, and he owned extensive property in town.

From 1850 onward Bishop displayed an entrepreneurial spirit of diversification beyond the artisan’s trade he had mastered. As Carl R. Lounsbury relates in Architects and Builders in North Carolina, New Bernians Alonzo Willis and George Bishop were “probably the first mass producers of steam-manufactured building materials in North Carolina. Both men started their careers learning the traditional methods of joinery but ended them as proponents as industrialized manufacturing. As craftsmen seeking to expand the scope and volume of their shops, Willis and Bishop recognized that the traditional labor-intensive methods were insufficient to meet the demands of any market that reached beyond the local one.”

New Bern’s location on the Neuse River and its access to markets inland as far as Goldsboro and Smithfield evidently made it worthwhile to invest in the necessary equipment for producing goods with steam power. In 1848 Alonzo Willis began his factory on Union Point at the foot of Front Street with equipment he had acquired in the North and advertised his manufacture of sash, blinds, and doors “at short notice, and at New York prices.” In 1850 Bishop added production of building materials to his furniture making shop and construction business, promising prices “as cheap as can be bought in the state.” The arrival of the railroad in 1858 enlarged the markets for both men’s goods. In 1860, when there were five sash and blind factories in the state, Bishop’s was the largest, with eleven workers producing more than $8,000 worth of sash, blinds, doors, and moldings.

Newspaper articles track Bishop’s stages of diversification and expansion. Early in 1850, he announced in local papers including the Eastern Carolina Republican and the Newbernian and North Carolina Advocate that he had commenced a business on Market Street as a cabinetmaker and undertaker. He would have on hand a variety of furnishings, repair old furniture, make coffins, and attend to the burial of the dead. He also noted that he was continuing the “House Carpentering business.” By the end of 1850 he advertised that he had moved to Middle Street and had added the manufacture of sash and blinds, “made to order, cheap,” to his other lines of work (Eastern Carolina Republican, December 18, 1850).

By 1854, the sash and blind department took on greater importance, as Bishop noted that he had window sash, blinds, and panel doors “of a Superior quality kept constantly on hand and made to order at short notice as cheap as can be bought in the State, (or perchance cheaper)” (Atlantic, March 21, 1854); he also continued as a dealer in and manufacturer of cabinet furniture and in the undertaking business, but he did not mention his construction business. Similar advertisements continued for several years.

In 1856 and subsequent years, Bishop published a large and striking advertisement promoting his “Steam Variety Works” on Broad Street (New Bern Weekly Union, October 15, 1856, September 16, 1857, March 30, 1858) and showing a drawing of “George Bishop’s Variety Works,” a large, 2-story building, complete with a smoking chimney. Here he manufactured for wholesale or retail sales window sash, blinds, and panel doors, along with window and door casings, moldings, and window frames, all “at prices that will defy competition.” He still continued his furniture and undertaking businesses. By 1858 he had added brackets, balusters, and newels to his repertoire and noted that his sash mill was on Broad Street and his “Ware Rooms” on Middle Street (Newbern Daily Progess, September 25, 1858). The New Bern New Era (October 26, 1858) carried a column promoting local industry and citing Bishop as a man who had “labored assiduously for years to convince the public that certain works of handicraft can be manufactured here for their use, which renders the loss of time and money in obtaining them from the North and East unnecessary,” and which resulted in money flowing to local citizens rather than to distant recipients.

In 1859, the New Era reported a disastrous fire on January 17 at Bishop’s “Steam Factory Works” on Broad Street. The fire consumed the lumber in the yard, as well as the buildings and machinery. Bishop rushed from his downtown shop too late to salvage his manufacturing business. Firemen prevented the fire from destroying Bishop’s residence, which was “situated right in front of his machine shops.” Although Bishop suffered extensive financial losses, the newspaper predicted that he would soon rebuild and again give employment to “a large number of mechanics.” He continued to run his usual advertisements even as he rebuilt.

Within a few months, according to the Daily Delta of June 21, 1859, a new brick building for Bishop’s steam Sash and Blind Factory was under construction at a new site, near the northwest corner of Queen and Hancock Streets; it promised to be a “fine structure” that would benefit the appearance of “that part of our burg.” By August 12 the Newbern Daily Progress reported that Bishop was receiving his new machinery and would soon have it in operation in his “new and spacious brick Furniture shop, near the R. R. station. Judging from the size of the boiler, which we saw him rolling off of a car in front of the shop yesterday, we should think he will have power enough to do quite an extensive business.”

Bishop had used the fire to advantage by moving his shop to a location near the newly completed railroad that would maximize his access to markets and suppliers. By September, he had changed his regular advertisement to identify his “Sash Mill” on Hancock Street. The Newbern Daily Progress of October 18, 1859, announced, “Our friend Bishop met with a heavy loss last winter by being burnt out, but his energy overcomes all obstacles, and he will soon be operating again on a much larger scale than formerly.”

During the Civil War, Bishop advertised for sale 125 “Tray Wheel-Barrows, built for throwing up earth-works, &c.,” for which he surely anticipated a market among those creating the defenses for New Bern (Newbern Weekly Progress, October 15, 1861). He served as a second lieutenant in the 19th Regiment of North Carolina Troops, 2nd Cavalry and fought in the Battle of New Bern in 1862, a battle won by Union troops who then occupied New Bern for the remainder of the war.

After the war, Bishop renewed his construction business. He contracted for the rebuilding of Christ Church after it burned in 1871, and in 1872 the New Berne Times of August 16 noted that Bishop and (brickmason) William Jones were erecting brick buildings on Middle Street for Dr. Hughes. The buildings, which have not been identified, showed “the great improvement made of late in the builders art,” with roofs in the “mansard” mode. In 1873 Bishop was one of nine directors elected for the Citizens’ Loan and Building Association (New Berne Times, June 8, 1873).

In 1874, Bishop was again advertising his manufacturing business. Not citing his cabinet shop or undertaking business, he featured in the Republic and Courier of July 18 his production of doors, sash, blinds, brackets, moldings, etc. and noted, “In order to prevent persons in need of such work from sending their money out of the State, we sell Sash and Blinds at the following prices.” He also continued or renewed his engagement in the undertaking business.

Bishop found other ways to employ his steam engine and other equipment. The Daily Journal of July 1, 1882, noted that he was “preparing to start his grist mill again,” and, in a relatively new enterprise, “sawing lumber all the spring for truck boxes.” The local economy by this time included truck farming, meaning commercial production of food for shipment, which created a profitable if seasonal local market for manufacture of wooden shipping boxes. The Daily Journal of February 25, 1888, noted that Bishop’s “box factory” on Hancock Street was “kept busy during the trucking season.” By 1898, the Daily Journal of January 16 reported repairs being made to rear of Bishop’s factory on Hancock St., “now used as a box factory.”

Operation of factories powered by steam was always a perilous business. The Daily Journal of April 4, 1883, reported that the previous day the boiler at Bishop’s saw mill on Hancock Street near the railroad depot “exploded with a tremendous noise, jarring houses in every part of the city.” The fireman was killed, and Bishop and another man who were in an adjoining room “made a narrow escape, Mr. Bishop being buried quite up to his waist in brick and mortar and receiving some slight injury.” Bricks, timber, and pieces of the boiler were flung considerable distances. The cause of the explosion was not identified.

George Bishop married twice, first in 1847 to Eliza B. Good (1827-1849), a daughter of carpenter Benjamin C. Good. Through Eliza, Bishop became involved in a lengthy effort to emancipate an enslaved man named John Good, whom she had inherited from her father and who had become Bishop’s property. Bishop worked persistently to attain John Good’s freedom, which was accomplished by an act of the state legislature in 1854-1855. (See Note below.) After Eliza’s death, George remarried, to Eliza Jane Kilpatrick (?) (1826-1898), and the couple had several children. By 1882, Bishop and his family resided in a two-story house on New (Neuse) Street, which had formerly been the home of antebellum black leader John C. Stanly (Daily Journal, September 3, 1882), and in 1887 the Daily Journal of September 30 reported that he was building an addition to the house.

George Bishop died on June 9, 1901, while on a visit to family at Morehead. He was buried at Cedar Grove cemetery in New Bern. He was noted as a respected citizen, a native of New Bern, and a member of Christ Church.

Note: In 1848, George Bishop placed a notice in the Newbernian and North Carolina Advocate of November 21 and subsequent issues that he planned to apply to the General Assembly “for the passage of an act, emancipating my slave, John Good.” As reported in the New Bern Advocate (December 26, 1848), legislator William H. Washington introduced a bill to the state legislature to emancipate Good and provided a detailed account of the background. Washington stated that although he was opposed to general emancipation of slaves, “this was a peculiar case.” He explained that Good’s original owner (Benjamin C. Good) was so “exceedingly anxious for his emancipation, that he not only enjoined it on his representatives and legatees, but made it an express condition upon which the legatees should take his property” as specified in his will. (Benjamin C. Good’s will stipulated, “I give my Mulatto boy Jack his freedom when he arrives to the Age of Twentyfive and in case my Heirs do not give said boy his time, they shall forfeit their Heirship to any of my estate” [Ancestry.com]. Benjamin C. Good’s estates papers may provide further details.)

Washington further explained that Benjamin C. Good’s estate had become “much diminished,” and his two young daughters became “dependent for support upon the exertions of the boy John; and although the Will of his master provided for his emancipation, at the age of twenty-one years [sic], he labored most assiduously for their support and maintenance, until they were grown, and he about thirty years of age.” By 1848, one of the two daughters had died, and the other (Eliza) had married George Bishop in 1847, which made Bishop the legal owner of John Good. Bishop “united in a deed of manumission” for John Good, which accompanied the bill.

At the time Benjamin Good made his will in 1827, private manumissions were difficult but possible. The process had become almost impossible by the 1840s. Moreover, state law required the newly freed person to leave the state. As Washington explained, because John Good was “very unwilling to leave the State,” his owner, George Bishop, had applied to the legislature to pass a bill to allow him to remain, and provided a petition signed by “many of the most respectable citizens” of New Bern that he was “honest, sober, industrious, and useful to the Town” (New Bern Advocate (December 26, 1848). Apparently this effort failed, and Eliza Good Bishop died in July 1849 without seeing John Good freed.

Yet Bishop persisted in the cause. In 1854, the legislature again took up an act to emancipate John Good, which was supported by a memorial signed by many citizens of Craven County, (Raleigh Register, December 16, 1854; Charlotte Democrat, March 2, 1855). The Newbern Journal of December 20 identified Good as “one of our barbers” and commented, “There is not, in our opinion, a more deserving slave in the State of North Carolina.” This time the act passed, stating that “John Good, a slave, the property of George Bishop. . . with the consent and at the request of the said owner,” would be set free, and that a bond of $1,000 be posted to guarantee his good behavior while in the state and that he would not become a burden to the county. It was ratified January 20, 1855 (William L. Byrd III, In Full Force and Virtue: North Carolina Emancipation Bonds, 1713-1860), 308-309.

The United States Census of 1860 listed John R. Good as a free mulatto barber, aged 45, with one John Banton in his household. (Curiously, the 1850 census also listed a John Good, mulatto barber, 35, with Banton in his household; at that point the barber still belonged to George Bishop but may have been living essentially as a free man and so recorded by the census. ) John R. Good continued as a well-known barber in New Bern. He became a political leader in New Bern during and after the Civil War and took a prominent role in the Freedmen’s Convention of 1865 (Bishir, Crafting Lives). He apparently died in 1880.

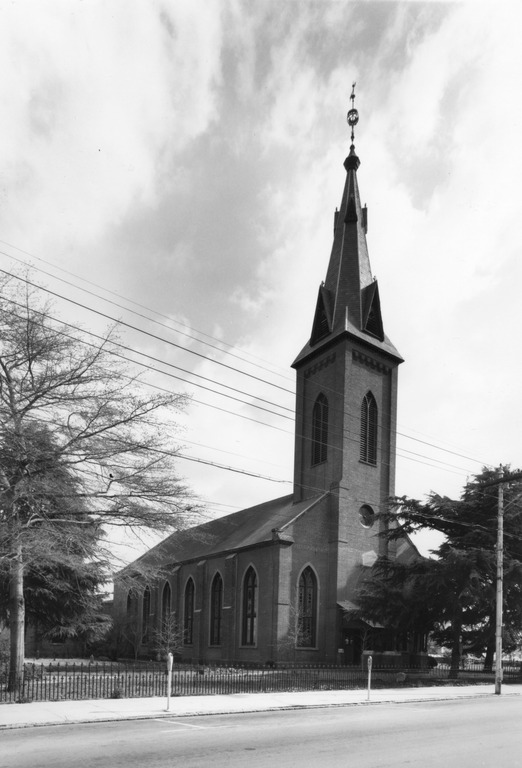

Christ Episcopal Church

Contributors:George Bishop, contractor (1871-1885); Bennett Flanner, brickmason (1821-1824); Thomas S. Gooding, builder and architect (1821-1824); Hardy B. Lane, Sr., carpenter/joiner (1821-1824); Wallace Moore, brickmason (1821-1824); Martin Stevenson, builder and architect (1821-1824)Dates:1821-1824; 1871-1885 [rebuilt]

Location:New Bern, Craven CountyStreet Address:320 Pollock St., New Bern, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Religious

Images Published In:Catherine W. Bishir, North Carolina Architecture (1990).

Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Eastern North Carolina (1996).

Peter B. Sandbeck, The Historic Architecture of New Bern and Craven County, North Carolina (1988).Note:Christ Episcopal Church in New Bern, built in 1821-1824, was one of the first Gothic Revival churches in North Carolina. Although the local newspaper cited Martin Stevenson and Thomas S. Gooding, local artisans, as “architects,” in 1820 the parish already had a plan for a church to be 70 by 55 feet, of brick, and with “high arched windows” before letting the contract. It was built of Flemish bond brickwork with pointed arched windows and a blending of Gothic Revival, Federal, and Greek Revival details. It is tempting to attribute some role in design to architect William Nichols, who had been in New Bern earlier, but there is no documentation of his role. Only the walls of this first period survive: after a fire in 1871 the church was rebuilt by George Bishop using the old walls. The image here shows the church after it was rebuilt following the fire. See Sandbeck, New Bern, and Bishir, North Carolina Architecture, for drawings of the 1820s church before the fire.

George Bishop Stores

Contributors:George Bishop, contractorDates:1885-1888

Location:New Bern, Craven CountyStreet Address:240-242 Middle St., New Bern, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Commercial

Images Published In:Peter B. Sandbeck, The Historic Architecture of New Bern and Craven County, North Carolina (1988).

Pennell House

Contributors:George Bishop, contractorDates:1890

Location:New Bern, Craven CountyStreet Address:George St., New Bern, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Residential

Note:New Bern’s Daily Journal of April 29, 1890 reported, “A handsome dwelling house is being erected on the lot on George street, near Pollock, for Mrs. W. H. Pennell, of Philadelphia. Mr. George Bishop is the contractor.” This house has not been identified, and it is unlikely that it is still standing.