Houser, William H. (ca. 1841-1912)

Birthplace:

South Carolina, USA

Residences:

- Charlotte, North Carolina

- Arkansas

Trades:

- Brickmason

- Brickmaker

NC Work Locations:

Building Types:

Styles & Forms:

Italianate

Born into slavery in South Carolina, brickmason and brickmaker William H. Houser (ca. 1841-1912) exemplifies the African-American artisans striving for economic success and community identity in the decades after the Civil War in a career that spanned years of opportunity and oppression. Trained in a trade long associated with free and enslaved black workmen, Houser parlayed brickwork into a large and thriving business in the growing city of Charlotte, N. C., erecting and supplying bricks for important buildings in the city and surrounding region. He also became a prominent member of the city’s black social and political leadership during the 1880s and 1890s, part of a group that historian Janette Thomas Greenwood treats in Bittersweet Legacy: The Black and White “Better Classes” in Charlotte, 1850-1910 (1994). For much of Houser’s career in Charlotte, African American artisans had opportunities to engage in entrepreneurial activities and to prosper; the local white-run newspapers frequently carried favorable stories about their accomplishments, including Houser and his distinguished son, physician Napoleon Bonaparte Houser. Toward the end of the century, however, as Greenwood relates, the Housers and others experienced the impacts of the state’s white supremacy crusade of 1898-1900, including the expansion of Jim Crow segregation policies and the disfranchisement of black men. In 1910 W. H. Houser joined his sons who had moved to Arkansas; he left in Charlotte a strong memory of his character and accomplishments and a legacy of substantial brick buildings.

William H. Houser’s parentage and early life have not been established, but he was a native of South Carolina who probably learned his trade while enslaved. By 1870 he was listed in the census in Gaston County, N. C. as a brickmason, a property owner, and head of a household. (See note below.) Like many black and white men in the building trades, W. H. Houser was drawn to the growing railroad town of Charlotte, where a spirit of entrepreneurship and industrial development created a demand for brickmakers and bricklayers. The Charlotte newspapers of the late 19th century regularly carried reports of construction projects there and in the industrializing communities nearby, noting the projects of entrepreneurs both black and white. In 1880, the census listed Houser (born about 1845) in Charlotte, a brickmason and head of a household that comprised his wife, Fannie, and four children, aged 17 down to 12. The sons were working as farm hands, and daughter Eliza was in school. The household also included William’s brother-in-law, William Lineberger, 30, also a brick mason, and his wife Lucy, a laundress. Living next door to the Houser family was brickmason William W. Smith, who would be associated with Houser in their joint trade.

Along with economic opportunities, the social and racial climate in Charlotte was remarkable for its time. Although there was not “social equality” between the races, there was often cooperation and mutual respect for ability as well as joint involvement in the temperance movement, which brought together many of the “better classes” of both races. As a successful and respectable businessman, family man, and prohibitionist, Houser was part of that group, as were the children he and his wife raised and educated. Houser became active in political life, including running (unsuccessfully) as “prohibition candidate” for the city’s board of aldermen (Charlotte Democrat, April 25, May 6, 1881). When W. H. Houser’s son Will Ed Houser (1864-1922), who followed in his father’s trade as a brickmason, married Amanda Yount in Newton, N. C., on May 7, 1889, the Newton Enterprise of May 10 headed the account, “A Fashionable Colored Wedding,” and noted that W. E., then of Charlotte, was accompanied by his brother N. B. and William J. Massey, a “promising bricklayer of Charlotte.” The report described W. H., the father of the groom, as “one of the leading contractors of the State for making and laying brick,” who was “engaged in a contract with the Southern Oil Trust Company for making and laying one million of brick.” (Will Ed Houser died in Newton, Catawba County, N. C., and was buried in Snow Hill cemetery there.)

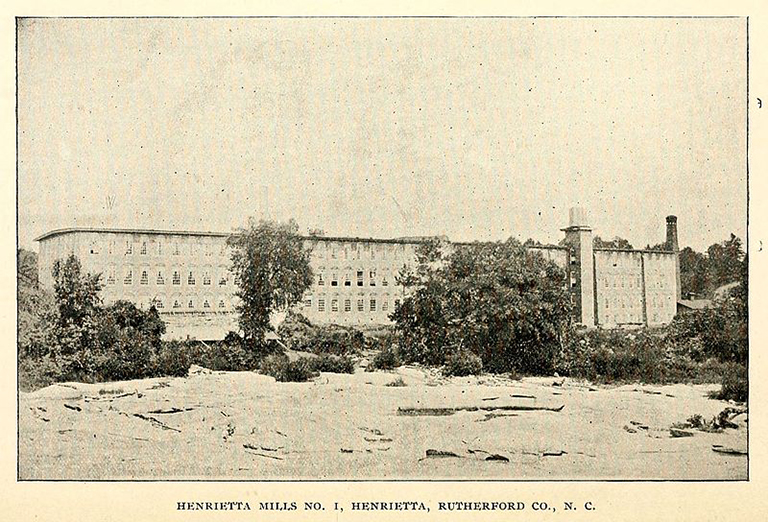

Gaining a reputation for good work and forming connections with Charlotte’s leading citizens, William H. Houser undertook the brickwork for a substantial number of buildings, and like some other brickmasons he also operated a brickyard. In 1887, the Charlotte Chronicle reported on December 25 that William H. Houser had “completed the erection of the buildings for the Henrietta Mills, in Rutherford County, and it is said that he has made a splendid job of it. Mr. J. S. Spencer, the president, and Mr. S. B. Tanner, the secretary and treasurer of the company, speak very highly of his work as a builder. Hawser [sic] has applications to build other mills in this section.” (No other mills of the many that rose in the region have been identified as Houser’s work thus far.)

Among recent buildings noted in the Charlotte Observer on August 19, 1894, was the “Friendship Colored Church” (Friendship Baptist Church) for which Houser was the builder. A few years later, the Observer reported on April 25, 1897, that Houser had the contract for the brickwork on the Women’s Exposition Building in Charlotte, a prestigious building designed by Charlotte architect Charles Christian Hook. Later that year, the Observer noted on December 14 that Houser had the contract for an addition to the Thompson Orphanage. Also in 1897 Houser was the brick contractor for a “factory block” built for S. Wittkowsky on West Fifth Street, for which his company had laid 700,000 bricks (Charlotte Observer, November 21, 1897). In 1898, as Janette Greenwood reports, Houser won the contract from developer E. D. Latta of the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company to make 200,000 bricks for a gas plant in Latta’s new suburb of Dilworth.

Like other prosperous black citizens, Houser invested in real estate and built rental houses. At the turn of the century he was one of the wealthiest black people in Charlotte. In 1900, the census recorded W. H. Houser as being born in July 1840 in South Carolina, with his wife Fannie, born in 1842. They reported that they had been married for 38 years—since 1862. None of their children was still in their home. By this time, Houser identified himself as a “Brickyard Owner.” Among Houser’s proteges was William W. Smith, a younger member of Charlotte’s African American community who gained a reputation not only as a brick contractor but also as a designer of buildings. Houser probably trained Smith and then made him a partner in the brickyard before Smith went out on his own. Smith and his wife led in the founding of the temperance-oriented Grace A. M. E. Church in Charlotte.

In 1898, Greenwood notes, Houser was the only African American in Charlotte engaged in industrial manufacturing, operating brickyards equipped with machinery for mass production. The Charlotte Observer of July 1, 1899 noted that he had “manufactured 50,676 brick yesterday” and called him “one of Charlotte’s most progressive and reliable colored citizens.” On February 16, 1900, the Charlotte Observer carried a report on “Houser’s New Brick Machine.” It stated that he had bought a brick machine that would “give him a brick-making plant than which there will not be a better in the South.” The Charlotte News reported on August 1, 1900, that “Houser, the brick maker, got back today from Winston, where he went ‘to see if they can beat me in making brick.’ He spent a day at the Winston Brick and Tile Co.”

The Charlotte Observer’s report of February 16, 1900, also identified Houser as “an honest, thrifty citizen, who is already worth $5,000 or $6,000 . . . and his white friends hope that his honesty, industry and thrift will continue to meet there just reward.” Such language from the white newspaper signaled that Houser displayed the attitude and diplomatic skills required to have productive relationships with the white citizenry.

Even as the political and racial climate in North Carolina worsened in the late 1890s, as Greenwood has explained, Houser and other black members of Charlotte’s “better classes” hoped that their friends in the city’s white “better classes” would enable them to weather the troubled time. White newspapers still mentioned certain black citizens favorably despite the growing tensions during the 1898-1900 “white supremacy crusades,” such as the comment of the Charlotte Observer of July 1, 1899, that Houser was “one of Charlotte’s most progressive and reliable colored citizens.”

From time to time, Houser’s property was subject to arson or suspected arson, for which no motive was given. It was possibly that his success as a black businessman drew the attacks on his property. In 1896 someone set fire to a row of rental houses he owned (Charlotte Democrat, July 27, 1896). The Charlotte News of May 6, 1902, reported that Houser’s brick plant located near the Thompson Orphanage had burned. The cause was unknown, but “the owner is inclined to believer that it was the work of an incendiary.” Houser estimated his loss at $6,000, and had $4,000 worth of insurance; he planned to rebuild at once. No motive or individual was cited for the fire. Just a few months earlier, on March 1, 1902, Houser had advertised in the Charlotte Observer a sale notice for his “Brick plant,” which consisted of “an engine, boiler, brick machine, cutting table, etc.”

Houser and his friends and relatives were intensely aware of the implications of the “white supremacy crusade.” On January 10, 1900, the Charlotte Observer reported that the “Young Men’s Working Club, of Friendship Church, colored,” had held a debate at Houser’s residence on South Brevard Street to address the question, “Resolved, That the proposed constitutional amendment is right.” H. S. Davis and Charles Anderson represented the affirmative and W. F. Thompson and Z. Alexander the negative. No indication was given as to the content of the arguments. This surely referred to the disfranchisement amendment (not yet ratified for North Carolina) which essentially prevented blacks from voting; it included a literacy test and a “grandfather” clause, the latter to allow illiterate whites to vote for a few years. As Greenwood has related, many of the “better classes” of black citizens hoped that they might escape the proposed white supremacist policies with the aid of the white citizens with whom they had connections. But in 1899 the state passed a Jim Crow law requiring racial segregation of railroad cars without regard to class: blacks could no longer sit in the first class coaches, a measure that one spokesman saw as an attempt to “humiliate the Negroes, especially the educated ones.” Streetcars were likewise segregated by separate seating areas. After the election of 1900 ratified the disfranchisement amendment, some of the “better classes” hoped that the United States Supreme Court would strike it down, but in vain. Some of them were sufficiently educated to pass the literacy test, but voting officials often prevented even literate blacks from registering or voting. Many black leaders chose to step out of politics and focus on “education, property ownership, morality, and economic advancement as the keys to race progress in the South” (Greenwood, Bittersweet Legacy, 224).

William H. Houser apparently fared well for the first years after 1900. He bought an additional brickyard in 1901 (Charlotte Observer, February 6, 1901). Also in 1901 he was one of several men who was associated with Warren C. Coleman of Concord in the International Industrial Business Union, a group that included several of North Carolina’s leading black citizens. In 1903 Houser was among the city’s wealthiest men of color. His wife Fannie died (date unknown), and he remarried in 1906 (Charlotte Observer, May 16, 1906) to a woman named Susie, with whom he soon had a daughter, Frances. He continued his business, including advertising in 1906 that he could also saw wood (Charlotte Observer, September 10, 1906).

In the meantime, Houser had seen at least three of his sons leave Charlotte, part of a larger exodus of black citizens. L. C. (Cephas), a brickmason, had become a foreman of the Srea Construction Company in Boston by the time his death at age 44 (Charlotte Observer, December 13, 1906). Two others had moved to Helena, Arkansas–first Charles, who also worked as a brickmason and then Napoleon Bonaparte, the successful physician. By 1910, William Houser, now in his 60s, joined his sons in Helena, where he was listed in the census as a head of household aged 64 with his wife, Susie, aged 36, schoolteacher born in Massachusetts, and daughter Frances, aged 3. Houser was noted as managing a pharmacy, evidently the business owned by his son Napoleon. When William died in Helena after a stroke in 1912, the Charlotte Observer noted him as “for many years one of Charlotte’s best-known colored citizens,” who had been living with his son in Helena for two years. He was “one of the city’s leading contractors, held in high esteem by members of both races.” His remains were brought to Charlotte, and his funeral was held at Friendship Baptist Church on September 29 (Charlotte Observer, September 29, 1912).

W. H. Houser’s son, Napoleon Bonaparte (N. B.) Houser (1869-1939), had an especially notable career. Born in Gastonia, N. C. as the youngest of six children of W. H. and Fannie Houser, N. B. Houser attended public schools in Charlotte, worked for a time at his father’s farm and later at his brick factory, and became his personal secretary. He obtained formal schooling from the hard-won educational institutions established for black students in North Carolina. After graduating from Charlotte’s Biddle University in 1887, N. B. Houser completed studies at the Leonard Medical School at Shaw University in Raleigh, began a successful medical practice in Charlotte, and was a founder and officer in the North Carolina Colored Medical Association. The Charlotte Observer of August 12, 1896 reported that Dr. N. B. Houser, “colored,” had plans for “a very pretty cottage which he will build on South Brevard street.”

In June 1901, N. B. Houser decided to leave Charlotte, probably because of the impact of disfranchisement and Jim Crow policies. He moved to Helena, Arkansas, joining his brother Charles, a brickmason, who was already there. Helena was the seat of the strongly black agricultural Phillips County. There N. B. prospered as a physician, founder of Black Diamond Pharmacy, civic leader, and property owner. His residence in Helena was described in 1911 as “one of the most substantial, most elegant and most complete residences among the colored population,” and he also owned several rental properties (Green Polonius Hamilton, Beacon Lights of the Race [1911]). N. B. probably encouraged his father to move to the community, where the older man lived from about 1910 until his death in 1912. Despite N. B. Houser’s success in Helena, his time there was cut short in 1920, when he decided to leave the area after the notorious “Elaine Massacre” of October 1919 in the nearby Phillips County community of Elaine. Black sharecroppers had formed a union seeking fairer treatment from landowners, and in one of the nation’s bloodiest events of racial violence, white mobs and soldiers attacked and killed more than 200 black sharecroppers and others. Once more pulling up stakes, Napoleon Bonaparte Houser returned to Charlotte in 1920 and reestablished his medical practice. At his death in 1939 the Charlotte Observer cited his as “one of the largest practices of any negro doctor in the Carolinas.” He was interred in Charlotte’s Pinewood Cemetery.

Note: In 1870 the census takers evidently recorded William H. Houser and his family twice in Gaston County, once in the South Point vicinity, and once in Dallas; perhaps the family moved between the two census takers’ visits. In the South Point entry, Houser was listed as 29 and his wife, Fannie, 28, and they and their five children from age 9 down to one year old were all listed as natives of South Carolina, indicating a recent move from South Carolina. But the census taker who recorded the Houser family in the same census as a resident of Dallas in Gaston County, noted him as a brickmason aged 26, with wife Fannie of South Carolina and 4 children born in North Carolina. The names of the family make clear that both entries were for the same family.

- Janette Thomas Greenwood, Bittersweet Legacy: The Black and White “Better Classes” in Charlotte, 1850-1910 (1994).

- Green Polonius Hamilton, Beacon Lights of the Race (1911).

- Thomas W. Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City: Race, Class and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875-1975 (1998).

- Blake Wintory, “Napoleon Bonaparte Houser” (2009), The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspxentryID=5466.

Carter Hall

Contributors:William H. Houser, brickmasonDates:1895

Location:Charlotte, Mecklenburg CountyStreet Address:100 Beatties Ford Rd., Johnson C. Smith University campus, Charlotte, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Note:The imposing brick dormitory with corner towers was cited in “Beacon Lights” as Houser’s work—the magnificent Boys Dormitory—and its brickwork is an impressive display of his craft. The school for black students, initially called Henry J. Biddle Institute, was founded at another site shortly after the Civil War before moving to this site and becoming Biddle University in 1883. It was renamed in 1921 after the husband of a major donor. Whether Houser built or supplied bricks for any of the other buildings on campus is not yet known.

Friendship Baptist Church

Contributors:William H. Houser, brickmasonDates:Ca. 1894

Location:Charlotte, Mecklenburg CountyStreet Address:Corner of E. First St. and S. Brevard St., Charlotte, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Religious

Note:The present Friendship Missionary Baptist Church on Beatties Ford Road was organized in 1890 when forty members of First Baptist Church at 1021 S. Church Street withdrew and formed a new congregation. After several years, a new site was found at the corner of E. First and S. Brevard streets, probably the location of the church Houser erected. In 1970 the congregation moved to its current location on Beatties Ford Road.

Henrietta Mills

Contributors:William H. Houser, brickmasonDates:1887

Location:Henrietta, Rutherford CountyStreet Address:Henrietta, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Industrial

Note:There were two very large mills at Henrietta, including the Henrietta Mill #1 that Houser built. Both have been destroyed.

Women's Exposition Building

Contributors:C. C. Hook, architect; William H. Houser, brickmasonDates:1897

Location:Charlotte, Mecklenburg CountyStreet Address:Charlotte, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Educational

Women's Exposition Building

Contributors:C. C. Hook, architect; William H. Houser, brickmasonDates:1897

Location:Charlotte, Mecklenburg CountyStreet Address:Charlotte, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Educational