Lord, Anthony (1900-1993)

Variant Name(s):

Tony Lord

Birthplace:

Asheville, N. C.

Residences:

- Asheville, N. C.

Trades:

- Architect

NC Work Locations:

Building Types:

Styles & Forms:

Modernist; International style; Arts and Crafts; Tudor Revival

Anthony (Tony) Lord (February 17, 1900-December 9, 1993), one of Asheville’s most distinguished architects, was unusual among them in being a native son. His father was Asheville architect William H. Lord (1864 -1933), in whose office young Tony spent many hours; their firm of Lord and Lord began in 1929.

Although he began his career at an inauspicious time for Asheville and the nation, Anthony Lord developed a successful practice that encompassed varied building types in Asheville and Western North Carolina. He was flexible in his approach to style, embracing modernism but also working easily in more traditional modes. During World War II, he was among the founders of Six Associates, which became the major architectural firm in Western North Carolina. He was known and admired as a public-spirited citizen and an accomplished artist and craftsman.

According to his obituary, Anthony Lord was born to William Henry and Helen Lord and lived for “nearly his whole life” in the home designed and built by his father, located on Flint Street in the Montford Park suburb. Lord graduated from the Asheville High School in 1918 and received a degree in mechanical engineering from the Georgia School of Technology (Georgia Tech) in 1922. After studying art in New York he graduated from Yale University with a fine arts degree, and while there he was awarded the AIA medal for 1927. After traveling and drawing, painting, and photographing in Europe, he returned to Asheville and went into practice with his father, who died in 1933.

During the lean years of the Depression, which hit Asheville especially hard, Lord made a living by establishing the Flint Architectural Forgings, where he produced metal work for major projects including the National Cathedral in Washington and homes in Biltmore Forest near Asheville. As he said in an interview in 1993, “At that time it was all iron work. That was the period of the Depression. Nobody built anything and architects were completely unemployed.” One of his few architectural projects during these years was the Dillingham Presbyterian Church (1934), in rural Buncombe County, a beautifully simple stone building; members of the congregation gathered rocks from fields and the Big Ivy River and provided and sawed the timber at Vestal Dillingham’s local sawmill (Asheville Citizen-Times, November 29, 2001).

Although Lord gained a few residential commissions in the late 1930s, the 1938-1939 Asheville Citizen-Times Building was his first major architectural work. The newspaper owners needed to build quickly, having been evicted from their former site. The company, Lord recalled, only had 15 months to plan the new building and build it. He explained that newspaper owner “Hiden Ramsey got me to do it, and my little office didn’t do anything else for a solid 15 months. We did it days, nights, and Sundays” (Lord interview, 1990, quoted in _Asheville Citizen-Times_, May 11, 2002). It was one of the first big building projects in Asheville after the hiatus in private building during the Depression, and its prominence and modernist style, especially its bands of glass block windows, captured widespread attention as a sign of renewed progress.

In 1940, Lord was employed on another attention-getting modernist building: the Sprinza Weizenblatt House in Asheville, designed by Marcel Breuer, the famed Bauhaus architect, with Lord as associate architect (_Asheville Citizen-Times_, September 19, 1940, building permit recorded). Breuer visited the innovative Black Mountain College a few miles from Asheville and became acquainted with Dr. Weizenblatt, a Viennese ophthamalogist who had moved to Asheville and who also attended events there. Lord, engaged to prepare specifications and supervise construction, recalled that Dr. Weizenblatt was a lively woman who “wanted the new thing.” Lord remembered that although the design was novel, the construction with local stone was “nothing unusual” (see Bishir, _North Carolina Architecture_).

With these projects, Lord showed his interest in modernist architecture in its earliest phases in North Carolina. In 1941, when the North Carolina chapter of the American Institute of Architects met in Asheville during Lord’s presidency, Lord was “in charge of the arrangements for the institute sessions,” and Marcel Breuer was the featured speaker at the meeting at the Pisgah Inn; his remarks discussed “new ways to use familiar materials,” and “the aesthetic aspects of modern architecture” (_Asheville Citizen-Times_, July 13, 1941).

No sooner had construction begun again after the Great Depression than the onset of World War II and its limitations on construction materials brought more challenges to architects and builders. In 1941, as noted above, Anthony Lord and other architects in Asheville and Western North Carolina formed Six Associates, who joined forces to have enough staff to gain wartime government contracts. The group continued after the war and became the leading architectural firm in Western North Carolina. Lord’s and Six Associates’ work generally represented various strains of modernism. Lord commented in 1993 on his preference for modernist design rather than the traditional styles many residential clients wanted: “I did two or three neo-Georgian adaptations for houses. They did not make sense. They represented something which did not exist.”

Among the architectural projects cited in Lord’s obituary were the following: the Asheville Citizen-Times Building, the Dillingham Presbyterian Church, the Music House at the Asheville School, and the Doan Ogden House. Also included were several projects generally credited to Six Associates such as the American ENKA Administration Building (see Six Associates Building List), and campus buildings at Warren Wilson College, Western Carolina University, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and the University of North Carolina at Asheville. Best known among Lord’s designs at the University of North Carolina at Asheville is the Hiden Ramsey Library of 1963, an imposing blend of modernism and classicism. Lord retired from architectural practice in 1970.

Anthony Lord was active in many civic and professional organizations and was a leader in promoting development of libraries and natural resources including tree planting in Asheville. He served as president of the North Carolina Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (1940-1941), and in 1971 he was named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects. According to _Anthony Lord: A Retrospective_ (1984), he “considered his _real_ accomplishments the growth of the Pack Memorial Library, trees in downtown Asheville, and _The Arts Journal_.” The Pack Library in Asheville has a large collection of Six Associates documents including many related to Anthony Lord.

_Anthony Lord: A Retrospective_ (1984), published by the Asheville Art Museum.

Oral history with Anthony Lord (1993) at http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/oralhistory/VOA/documents/lord_tony_transcript.pdf.

Pack Library exhibit on Anthony Lord (2002) at https://packlibraryncroom.wordpress.com/2014/08/02/anthony-lord-artist-architect-craftsman-2/

Asheville Citizen-Times Building

Contributors:Anthony Lord, architectDates:1938-1939

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:14 O’Henry Ave

Status:Standing

Type:Commercial

Images Published In:Catherine W. Bishir, Michael T. Southern, and Jennifer F. Martin, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Western North Carolina (1999).

Note:With Asheville struggling during the Great Depression, the commission for the newspaper building was an especially welcome opportunity for local architects and builders. It is described as Anthony Lord’s first large-scale architectural project. The dignified, asymmetrically composed structure presents a classic example of the International style with cleanly expressed forms in limestone and glass block. Lord also made the brass and terrazzo map of Western North Carolina for the lobby entrance floor in the Citizen-Times Building.

Crawford Music House, Asheville School

Contributors:Lord, Anthony, architectDates:1937

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:Asheville School Road, Asheville, Buncombe County

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Note:Lord continued the school’s a picturesque Tudor Revival style with its scholarly and English overtones considered suitable to a preparatory school. He also designed the stylistically related Memorial Hall (1947) on the campus.

D. Hiden Ramsey Library

Contributors:Lord, Anthony, architectDates:1963

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:University of North Carolina at Asheville

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Images Published In:Anthony Lord: A Retrospective (1984).

Note:The most prominent of Anthony Lord’s buildings at UNC-A, the library at the heart of the campus features the period’s use of clean, modernist forms in a classically influenced composition with a tall central portico and pilasters separating tall window bays.

Dillingham Presbyterian Church

Contributors:Lord, Anthony, architect; Charles Taylor, Alfred Dillingham, Will Jarrett, Stamey Carter, and Hensley Brothers, buildersDates:1934

Location:Dillingham, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:SR2203, Dillingham, Buncombe County

Status:Standing

Type:Religious

Images Published In:Anthony Lord: A Retrospective (1984).

Note:The small, beautifully composed church makes effective use of the local river rock widely used in the community. Designed by architect Lord, it was built by local craftsmen well versed in the tradition. It exemplifies Western North Carolina’s architects’ integration of familiar crafts traditions with the Arts and Crafts movement.

Doan Ogden House

Contributors:Lord, Anthony, architectDates:1951

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:175 Lakewood Dr., Asheville, Buncombe County

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:Anthony Lord designed the modernist residence for nationally known landscape architect Doan Ogden, who had moved to North Carolina to teach at Warren Wilson College. The clean-lined house with broad expanses of glass is integrated into the natural landscape. A pioneer in introducing native species into naturally planned gardens, Ogden also designed the Botanical Gardens at Asheville near the University of North Carolina at Asheville, and many other landscapes and gardens in the region.

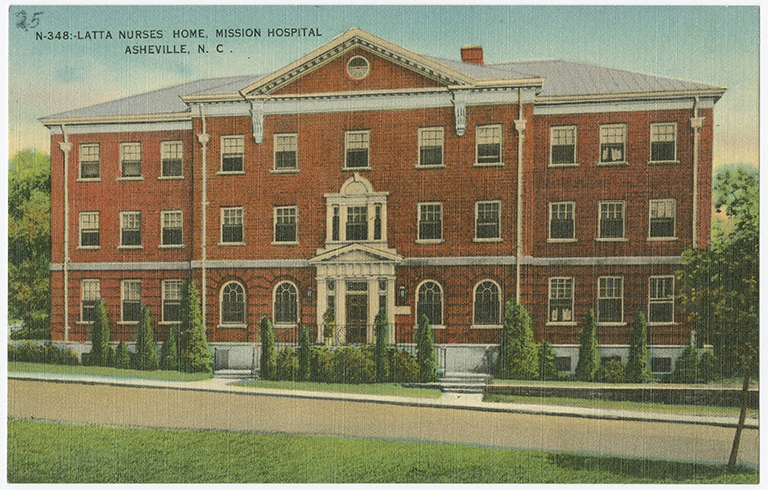

E. D. Latta Nurses' Home

Contributors:Anthony Lord, architect; Lord & Lord Architects, architects; William H. Lord, architectDates:1929

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:59 Woodfin Pl., Asheville, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Health Care

Note:This is now known as the Interchange Building.

Sprinza Weizenblatt House

Contributors:Lord, Anthony, supervising architect; Marcel Breuer, architectDates:1940-1941

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:46 Marlborough Rd., Asheville, Buncombe County

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Images Published In:Catherine W. Bishir, North Carolina Architecture (1990); Catherine W. Bishir, Michael T. Southern, and Jennifer F. Martin

The Historic Architecture of Western North Carolina (1999).Note:Dr. Weizenblatt, a Viennese opthamalogist, commissioned leading modernist Marcel Breuer, who had come to the area in connection with the avant-garde Black Mountain College, to plan her duplex residence of stone and wood in a clean, modernist style that contrasted with the generally revivalist architecture of its neighbors in the Lakeview Park suburb. It is among the earliest, if not the earliest, thorough-going International Style residences in the state. Tony Lord served as local superintending architect, an experience that dovetailed with his preference for modernist design. In a letter of May 21, 1940 (Marcel Breuer Digital Archive at the Syracuse University Libraries) Breuer wrote to Dr. Weizenblatt of his pleasure in making her acquaintance “in Asheville, last Thursday, the 16th,” summarized their discussion about the proposed two-family house, and stated that he had started with sketches and planned to send them soon. The Marcel Breuer Digital Archive at Syracuse University Libraries also includes drawings and photographs for the project.

St. Mark's Lutheran Church

Contributors:Anthony Lord, architect; Lord & Lord Architects, architects; William H. Lord, architectDates:1930

Location:Asheville, Buncombe CountyStreet Address:10 N. Liberty St., Asheville, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Religious

Note:See Pack SA1076, A1078, SA1079, and ARD0059, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville.