Salter, James A. (1874-1939)

Variant Name(s):

James Armstrong Salter

Birthplace:

Eau Claire, Wisconsin, USA

Residences:

- Raleigh, North Carolina

Trades:

- Architect

Building Types:

Styles & Forms:

Beaux-Arts; Georgian Revival; Tudor Revival

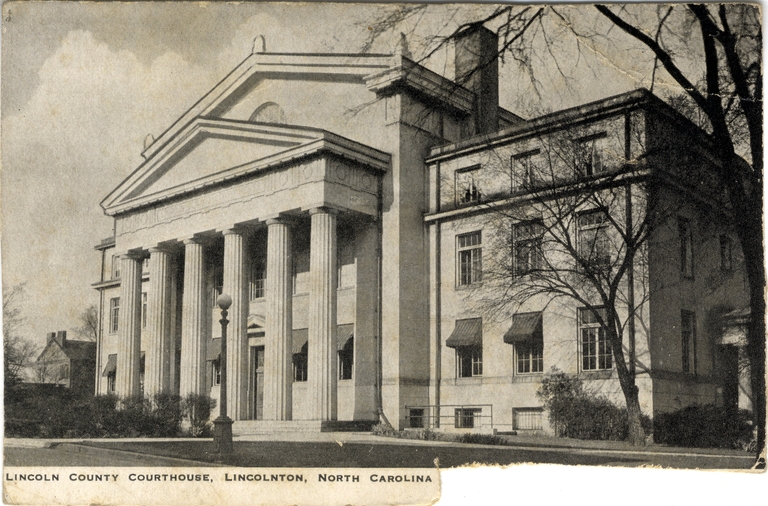

James Armstrong Salter (1874-1939), a native of Wisconsin, was among Raleigh’s leading architects from the early 1910s until his death and served as State Architect from 1919 to 1921. Skilled in various styles and building types, he is credited with designing approximately thirty buildings in North Carolina, most of which were residences and educational buildings in Georgian Revival and other revival styles and neoclassical public buildings such as the Lincoln County Courthouse.

Salter was born in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, on April 23, 1874. He attended secondary school in Rochester, New York, and went on to attend the Rochester Athenaeum and Mechanics Institute. He apprenticed in the office of noted Rochester architect J. Foster Warner from 1895 to 1900 and worked independently in Rochester from 1900 to about 1911.

The year of Salter’s arrival in Raleigh is unknown, as are his reasons for moving to the city. Advertisements for his architectural practice appear in Raleigh newspapers as early as 1913. By 1915 and for several years afterward, as shown in the Raleigh city directory, Salter employed as a draftsman Thomas Wright Cooper, a former stonecutter who would become a notable architect in his own right.

Salter quickly made connections and gained commissions among leading citizens, as demonstrated by some of his earliest known projects in North Carolina. The Andrews-London House (ca. 1916) located on Raleigh’s prestigious North Blount Street, is an imposing yet whimsical take on the Georgian Revival style in red brick with unusually bold classical details. The Capital Apartments (ca. 1917), a block east of the State Capitol near Christ Episcopal Church, was the city’s first multistory, modern apartment building, a 5-story Beaux Arts edifice of buff brick features a central courtyard, inset balconies, and a heavy cornice with paired curving brackets. The project was conceived, managed and financed by the Capital Apartments Corporation, of which Salter was a shareholder along with influential Raleigh builder C. V. York (1876-1941), who was the contractor for the building. Salter’s status as a corporate shareholder indicates that he had already established solid relationships with Raleigh’s business leaders. Around 1917 a prosperous cotton mill owner hired Salter to design the Aldridge Vann House (1918) for his residence in Franklinton. Salter’s beautiful pencil sketches depict three preliminary designs, and the final blueprints combine the Craftsman and Italian villa details depicted on two of the pencil drawings. The U-shaped house of buff-colored brick features massive eave brackets akin to the Capital Apartments.

Salter described himself as self-employed when he registered for the draft in 1918 during World War I. For a brief period, he worked in a partnership with architect G. Murray Nelson, a Canadian who arrived in Raleigh in 1918 or 1919 and first appeared in the Raleigh City Directory as partner with Salter in 1919 (the only year the directory listed “Salter and Nelson”). With Nelson, Salter designed the Gilmer’s Department Store in Raleigh (completed 1921) and the Lincoln County Courthouse (completed 1923). By 1921, Salter was operating on his own, and his former associates G. Murray Nelson and Thomas W. Cooper formed the firm of Nelson and Cooper.

Meanwhile, in May of 1919, Salter had been appointed State Architect of North Carolina, a position newly established by the state legislature. A bill introduced by Representative R. S. McCoin of Henderson in Vance County consolidated all of the design, engineering, drafting, and construction management functions of state-funded projects into one state-run office, that of the State Architect, which was overseen by the State Building Commission, which had been established in 1917. In an era when the state sought to maximize efficiency and economy to meet the immense postwar needs, McCoin believed this centralized model for state projects would lead to considerable cost savings over commissioning private sector architects on a project-by-project basis. (In the early 19th century, William Nichols held the official position of State Architect, but such an office was rarely in effect in North Carolina.)

As State Architect, Salter was paid an annual salary of $5,000, less than market value for an established architect at the time. As the Wilmington, North Carolina Morning Star reported on May 20, 1919, “The Building Commission had a large number of application[s], but the majority were young and inexperienced architects. The older men in the profession would not consider the job, which would have required them to do a large amount of work at a price which is a great deal smaller than the regular commissions on the same amount of work.” Salter agreed to take the job on the condition that it would be part-time (consisting of advising the Building Commission and supervising the work of “various architects for state buildings”) and that he would be allowed to continue working in the private sector. A few state buildings dating from Salter’s service as State Architect have been identified; it is likely there are many more.

The office kept busy on numerous projects, and representatives of both the State Building Commission and specific institutions lauded the economies and efficiencies that resulted. In October 1920, “state architect” Salter stopped in Charlotte on his way back from Lincolnton to Raleigh and spoke with a reporter for the Charlotte News who reported in a front page story on October 30, that Salter “told of work recently completed and under construction by the state totaling considerably more than half a million dollars. There is hardly a state institution at which work is not in progress,” and there was more to come. “The rapid progress the state is making in education and the effort to improve conditions for the unfortunate are the reasons for the work that has been under taken and that will be undertaken.” Salter cited at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill a new dormitory (Steele Dormitory) under construction and a laundry and other improvements costing about $180,000; at the North Carolina College for Women in Greensboro a kitchen and new dormitory to cost about $300,000; at the East Carolina Teacher Training School in Greenville a wing to the East Dormitory, a remodeling of the administration building, and rebuilding of the heating plant for about $150,000; at the North Carolina State College in Raleigh, two dormitories and remodeling of Pullen Hall; plus extensive work at the Caswell Training School at Kinston. The account wound up by highlighting a major project to begin in 1921: a “half million dollar temple of agriculture at Raleigh” on Edenton Street. Half the required sum had been appropriated, and preliminary sketches had been seen. “It will be either of granite or limestone construction; and its architecture will make it a counterpart of the capitol, which was erected in 1832 and which is said to be the finest specimen of perfect architecture in the world.”

Not long after Salter returned to Raleigh in the fall of 1920, public controversies erupted that would result in his departure from the office and the abolition of the office. (The story of these events merits further study.) Late in 1920, as related in newspaper articles early in 1921, banker, lawyer and powerful University of North Carolina patron John Sprunt Hill of Durham lodged and made public a complaint against the office of the State Architect and Salter specifically, in which he raised objections to alleged delays and cost overruns for the construction of Steele Dormitory at the university. Moreover, in December of 1920, the State Treasurer asked Attorney General James Manning to render an opinion on the appropriateness of a $9,000 fee charged by the Office of the State Architect for inspection of newly erected buildings at the Caswell Training School in Kinston. The General Assembly appointed a committee to “make an investigation.” The Wilmington Morning Star of January 30, 1921 described a committee meeting held on January 28: “Investigation of the state building commission and the state architect by a selective committee was without any sensational developments. Heads of the state institutions, the Eastern Carolina Training school, the Caswell school and the North Carolina College for Women, testified today. Complaints of delays in getting plans came from all [,] but the summing up by Dr. J. I. Foust [president of the women’s college in Greensboro] was that the building commission and the architect are valuable agencies in the state’s building. John Sprunt Hill, represented by Judge R. H. Sykes of Durham, is the aggressor before the committee. He is a trustee of the university, and is charging gross malfeasance as the result of work done by Architect Salter for the institution. James H. Pou is defending Salter.” (Raleigh attorney Pou was a developer of Raleigh’s Hayes Barton suburb, where Salter designed several houses).

The controversy over the office of State Architect involved broader issues than the cost overrun and delays Hill cited. As related in Archibald Henderson’s history of the University of North Carolina (1949), The Campus of the First State University, at this time the leadership of the university had embarked on a grand plan for expanding the campus according to Beaux Arts concepts and the legislature had authorized substantial funds for the purpose. A principal element of the plan was creation of a second quadrangle south of the original campus, with South Building as the pivot. (See Arthur C. Nash.) The initial legislative acts funding the university expansion required oversight by the State Building Commission and the State Architect, and accordingly Salter designed and supervised work on Steele Dormitory, the first dormitory erected along the new south quadrangle. But according to an account by UNC president Harry W. Chase (quoted by Henderson, 274-275), university leaders wanted to put their project “into the hands of an architectural firm of recognized eminence” rather than working under the State Architect and the State Building Commission. Early in 1920 they engaged the firm of McKim, Mead and White of New York as consulting architects. John Sprunt Hill, chair of the “University Building Committee for the University Trustees” was “very active” in the process, and “there came to be some feeling in political circles that we were just a bit too independent of the Building Committee in what we were doing.” In Chase’s view, this “feeling” was the reason the hearings were called. After the legislative committee completed its investigation, recalled Chase, “the verdict was that the [state] Building Commission had done a good job and that it should be dismissed. So I suppose everybody was happy.” The legislature eliminated the Office of the State Architect on March 9, 1921. Thereafter the various state institutions employed their own architects.

Salter returned fulltime to private practice and during the 1920s and 1930s completed a number of commissions for private residences and institutional buildings. Some of these were initiated during his tenure as State Architect. At the Elizabeth City Normal and Industrial School, Salter began the design for Moore Hall while he was State Architect, and after he left office the school retained him to complete that building and other projects. By contrast, for the “temple of agriculture” Salter had described in 1920—the Beaux Arts classical style Agriculture Building on Edenton Street across from the State Capitol—the plans, dated January 22, 1922, are stamped by the Raleigh firm of Nelson and Cooper, Salter’s former associates. It is unknown if Salter had any role in their selection or in the design; the edifice was completed in 1923. Notably, H. A. Underwood (1888-1949), a member of the Nelson and Cooper firm, the engineer of record for the Agriculture Building, had worked under Salter in the State Architect’s Office as the Superintendent of Construction.

In the early 1920s, Salter again partnered with C. V. York as a shareholder, this time in the Raleigh Construction Company, the real estate development company that built the Sir Walter Hotel in which Salter was involved along with William L. Stoddart, a nationally known hotel architect; the Raleigh Times of March 3, 1922 reported that Salter had drawn the plans. He also designed the Henderson Graded School (ca. 1922) in Vance County, in Rep. McCoin’s district, and a high school in Lincolnton at about the same time. Around 1925, Salter’s former client Aldridge H. Vann hired him to design a brick consolidated school, the Franklinton Public School two doors away from his home. Salter also designed a number of residences for prominent Raleigh citizens. In addition to several houses in Raleigh’s Hayes Barton suburb, these include Longview (ca. 1925), a stone Georgian Revival house commissioned by Clarence Poe, the influential editor of the Progressive Farmer magazine; the Federal Revival style Rudolph Turk House (ca. 1932), built for a descendant of the long prominent Mordecai family, as the anchor of his suburban estate, Birdwood Farm; and the Eure House (ca. 1935), a Mount Vernon-influenced estate for Thad A. Eure, North Carolina Secretary of State from 1936 to 1988.

Salter married in the early 1930s, apparently for the first time, to Clair (Claire) Thomas, a widow, and they resided on Dawson Street in downtown Raleigh. In the late 1930s, he began construction of an elaborate residence for himself and his wife in Clarence Poe’s new Longview Gardens subdivision. The brick French Eclectic-style James A. Salter House, located on a prominent corner lot at the intersection of New Bern Avenue and North King Charles Road, was incomplete when Salter was struck by a car while walking on a winter evening in downtown Raleigh in 1939 and died of a fractured skull. He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. His widow and her adult daughter, Helen Thomas, stayed in the home on Dawson Street, where they resided in 1940.

- American Contractor, Vol. 31, Nr. 27 (July 2, 1910).

- “Annual Report to the Auditor of the State of North Carolina for the Seven Months Ending June 30, 1922” (1922).

- “Architect Elected,” Wilmington Morning Star, May 20, 1919.

- “Architect Saves Money,” Greensboro Daily News, May 17, 1920.

- “Building Going on for State,” Charlotte News, Oct. 30, 1920.

- “Choose State Architect,” Greensboro Daily News, May 17, 1919.

- Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University (1949).

- “James Armstrong Salter,” Who’s Who in the South (1927).

- M. Ruth Little, “Longview Gardens,” National Register of Historic Places nomination (2010).

- James S. Manning and Frank Nash, Biennial Report of the Attorney-General of the State of North Carolina, 1920-1922 (1922).

- “Minority Members in General Assembly Do Not Like Outlook,” Greensboro Daily News, Jan. 16, 1920.

- “Normal School to Have Many Improvements,” The Independent, Jul. 1, 1923.

- “Nothing Exciting in the State Architect Hearing,” Wilmington Morning Star, Jan. 30, 1921.

- McKelden Smith, “Agriculture Building,” National Register of Historic Places nomination (1976).

- Jule B. Warren, “Probe is Begun as to Architect,” The Charlotte News, Jan. 28, 1921.

Aldridge Vann House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1918

Location:Franklinton, Franklin CountyStreet Address:115 N. Main St., Franklinton, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:The residence was designed for Aldridge H. Vann, owner of Franklinton’s Sterling Cotton Mill. The landscape was designed by Thomas Meehan and Sons (Philadelphia) but is no longer intact.

Andrews-London House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1916

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:301 N. Blount St., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:The boldly detailed Georgian Revival dwelling was designed for Raleigh mayor Graham Andrews.

Capital Apartments

Contributors:James A. Salter, architect; C. V. York, contractorDates:1917

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:127 New Bern Pl., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:The eclectic high-rise apartment house was Raleigh’s first of its type and one of the finest early 20th century apartment houses in the state. It was built by the Capital Apartments Company, a corporation formed for the purpose, with contractor C. V. York taking a lead role and constructing the building. See the Raleigh News and Observer, November 16, 1916. The long article noted that the project leaders “give assurances that no convenience of comfort will be lacking. . . The bathrooms will be tiled, provided with built-in tubs and every other sanitary appliance that science has revealed.” “The erection of the apartment house, Raleighites are saying, is only another evidence that Raleigh is getting to be a city of proportions.”

Carr-Jones House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architect; Howard E. Satterfield, builderVariant Name(s):Adele Jones House

Dates:1931

Location:Warrenton, Warren CountyStreet Address:S. Main St., Warrenton, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:The prominent Georgian Revival red brick residence embodies an extensive remodeling of an existing antebellum house associated with the Elias Carr family.

Caswell Training School Powerhouse

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1920

Location:Kinston, Lenoir CountyStreet Address:Caswell Training School Campus, Kinston, NC

Status:Unknown

Type:Educational

Note:The Powerhouse was designed while Salter was serving as the State Architect. Salter also designed (unidentified) buildings for girls “middle and graded work.” The institution was the state’s only school for the mentally retarded until 1958.

Coke Apartments

Contributors:James A. Davidson, builder; James A. Salter, architectDates:1922

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:Corner of Hillsboro and McDowell Sts.

Status:No longer standing

Type:Residential

Note:Source: Davidson and Jones Archives; James A. Davidson Scrapbook, Charlotte Vestal Brown Papers, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Dormitory

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1920

Location:Greensboro, Guilford CountyStreet Address:University of North Carolina at Greensboro Campus, Greensboro, NC

Status:Unknown

Type:Educational

Note:Salter designed an unidentified dormitory at North Carolina Women’s College (today’s University of North Carolina at Greensboro).

East Dormitory

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1920

Location:Greenville, Pitt CountyStreet Address:Eastern Carolina University Campus, Greenville, NC

Status:Unknown

Type:Educational

Note:Salter designed an addition to East Dormitory at Eastern Carolina University.

Elizabeth City Normal and Industrial School

Contributors:James A. Salter, architect; J.J. Strand, contractorDates:1920s

Location:Elizabeth City, Pasquotank CountyStreet Address:Elizabeth City, NC

Status:Unknown

Type:Educational

Note:Some of the buildings were probably designed during Salter’s tenure as State Architect, others after he returned to private practice full time. Initially the school was a teacher training school for African Americans and is now Elizabeth City University.

Eure House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectVariant Name(s):Herford Hall

Dates:1935

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:2345 New Bern Ave., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:The Colonial Revival residence was from 1945 to 1983 the home of Thad and Minta Eure. Thad Eure was North Carolina Secretary of State from 1936 through 1989.

Flemming House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1922

Location:Oxford, Granville CountyStreet Address:207 Main St., Oxford, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Franklinton Public School

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1925

Location:Franklinton, Franklin CountyStreet Address:N. Main St., Franklinton, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Note:The design for the public school was commissioned by Aldridge H. Vann.

Fred A. Olds Elementary School

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectVariant Name(s):West Raleigh Grammar School

Dates:1927

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:204 Dixie Trail, Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Gilmer's Department Store

Contributors:G. Murray Nelson, architect; James A. Salter, architect; Salter and Nelson, architectsDates:1920s

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:Fayetteville St., Raleigh, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Commercial

Henderson Graded School

Contributors:Haynes and Son, contractors; James A. Salter, architectDates:1922

Location:Henderson, Vance CountyStreet Address:1000 S. Chesnut St., Henderson, NC

Status:Unknown

Type:Educational

House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectVariant Name(s):Dortsch House

Dates:1920

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:831 Wake Forest Rd., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:The brick Georgian Revival residence was expanded in the 1990s for use by the Bryan Lee funeral home. It is very similar to 821 Wake Forest Rd. which is attributed to Salter.

House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1920

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:821 Wake Forest Rd., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

James A. Salter House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1939

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:102 N. King Charles Rd., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:Salter was killed in a car accident while his home, a French eclectic design, was under construction.

Lincoln County Courthouse

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1921-1923

Location:Lincolnton, Lincoln CountyStreet Address:1 Courthouse Square, Lincolnton, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Public

Note:The Manufacturers’ Record noted in 1921 that “Salter and Nelson” (Thomas Nelson) had designed the Lincoln County Courthouse, which was to be in the “Greek Doric” order with 12 granite columns and to cost $200,000.

Longview

Contributors:James A. Davidson, builder; James A. Salter, architectVariant Name(s):Clarence Poe House

Dates:1925

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:Poe Dr.

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:Source: Davidson and Jones Archives, private collection. The Georgian Revival style stone residence was built for Clarence Poe, publisher of the Progressive Farmer magazine and developer of the Longview Gardens subdivision in Raleigh. The stone is said to have been quarried on his property.

Methodist Orphanage Administration Building

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1933

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:Glenwood Ave., Raleigh, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Educational

Mrs. John W. Drewry House

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:ca. 1924-1927

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:Raleigh, NC

Status:Unknown

Type:Residential

Mrs. W. H. Pleasants House

Contributors:Variant Name(s):Missouri Pleasants House

Dates:ca. 1927

Location:Louisburg, Franklin CountyStreet Address:Corner of Church St. and Sunset Ave., Louisburg, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:Satterfield’s building list includes a project for Mrs. W. H. Pleasants, Louisburg. On March 18, 1927, Satterfield wrote to Mrs. Pleasants (Missouri Alston Pleasants) requesting a meeting with her to discuss building her house. Local carpenter William Edens was involved in its construction, and an estimate for materials is addressed to him. A letter of February 14, 1927, from a building supply company in Raleigh to Mrs. Pleasants refers to a Mr. Salter, which may suggest that architect James A. Salter was also involved in the project. A second letter of the same date and authorship concerning the “tapestry” brick reports that the same brick was used in other projects including Mr. A. H. Vann’s house in Franklinton, designed by Salter; a Mr. Dameron’s house in Warrenton, and the Woman’s Club Building in Raleigh. Architectural drawings for the Pleasants house were in existence in Louisburg in 1986 (Charlotte Vestal Brown Papers, Special Collections Research Center, NCSU Libraries).

Pullen Hall

Contributors:William P. Rose, architect (1902); James A. Salter, architect (1920)Dates:1902; 1920 (remodeling)

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:North Carolina State University Campus, Raleigh, NC

Status:No longer standing

Type:Educational

Images Published In:Murray Scott Downs, North Carolina State University: A Pictorial History (1986).

Note:The Manufacturers’ Record (Feb. 20, 1902) reported that Rose was preparing plans for a building at the A&M College in Raleigh to contain a dining room, chapel, and library; this was the large building called Pullen Hall. The same announcement noted that (his former partner) Charles W. Barrett had provided plans to rebuild Watauga Hall, which had burned. James A. Salter did additional work in 1920; he also designed two unidentified dormitories at present NC State at about the same time. Pullen Hall burned in an arsonist’s fire in 1965; another building of the same name was built in 1987 at a different campus location.

Robert I. Lee House

Contributors:Coffey Family, contractors; John N. Coffey, contractor; John W. Coffey, contractor; John W. Coffey and Son, contractors; James A. Salter, architectDates:1936

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:1541 Caswell St., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Images Published In:Houses By Coffey, Charlotte Vestal Brown Papers, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Note:Tudor Revival residence.

Rudolph Turk House

Contributors:Coffey Family, contractors; John N. Coffey, contractor; John W. Coffey, contractor; John W. Coffey and Son, contractors; James A. Salter, architectVariant Name(s):Birdwood Farm

Dates:1933

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:13136 St. Alban’s Dr., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Images Published In:Houses By Coffey, Charlotte Vestal Brown Papers, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Note:Turk was a descendant of the Mordecai family, who owned extensive property in the area. The residence is now owned by Duke Raleigh Hospital and used as hospitality house.

S. Brown Shepherd House

Contributors:James A. Davidson, builder; James A. Salter, architectDates:1928

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:2405 Glenwood Ave.

Status:Standing

Type:Residential

Note:Source: Davidson and Jones Archives; James A. Davidson Scrapbook, Charlotte Vestal Brown Papers, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Sir Walter Hotel

Contributors:Dates:1922-1924

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:400 Fayetteville St., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Commercial

Images Published In:Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (2003).

State Agriculture Building

Contributors:Thomas Wright Cooper, architect; Nelson and Cooper, architects; G. Murray Nelson, architect; James A. Salter, preliminary architect; John E. Beaman, contractorDates:1922-1923

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:2 W. Edenton St., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Public

State School for the Blind and Deaf

Contributors:Carolina Construction Company, contractors; James A. Salter, architectVariant Name(s):Governor Morehead School

Dates:1924-1927

Location:Raleigh, Wake CountyStreet Address:Ashe Ave., Raleigh, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Steele Dormitory

Contributors:James A. Salter, architectDates:1920-1921

Location:Chapel Hill, Orange CountyStreet Address:University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Campus, Chapel Hill, NC

Status:Standing

Type:Educational

Note:The brick dormitory was planned during Salter’s tenure as state architect.